Researchers Justin Walsh of Chapman University and Alice Gorman of Flinder University in Australia took archaeology to a place it’s never gone before: space. The two were brainstorming ways of preserving historic space sites, like the sites on the Moon visited by the Apollo astronauts, when they came up with the idea for doing an archaeology project on the International Space Station (ISS).

“Space archaeology really seemed like something that was more theoretical than practical for a long time,” Walsh said. “And then I realized that the astronauts on the ISS have been taking pictures for decades and there are more photos of the space station than any other previous space habitat.”

According to Walsh, this made the ISS the ideal place for digital archaeology, which aims to study the material culture of a place through images. Archaeologists like Walsh and Gorman are interested in not only the objects and the built spaces but also the human relationship to those items—meaning the relationship between people and objects, objects and spaces, and people in space.

Justin Walsh receives an award from AIA for this and Alice Gorman’s SQuARE archaeological experiment.

Media Credit: Image courtesy of Justin Walsh

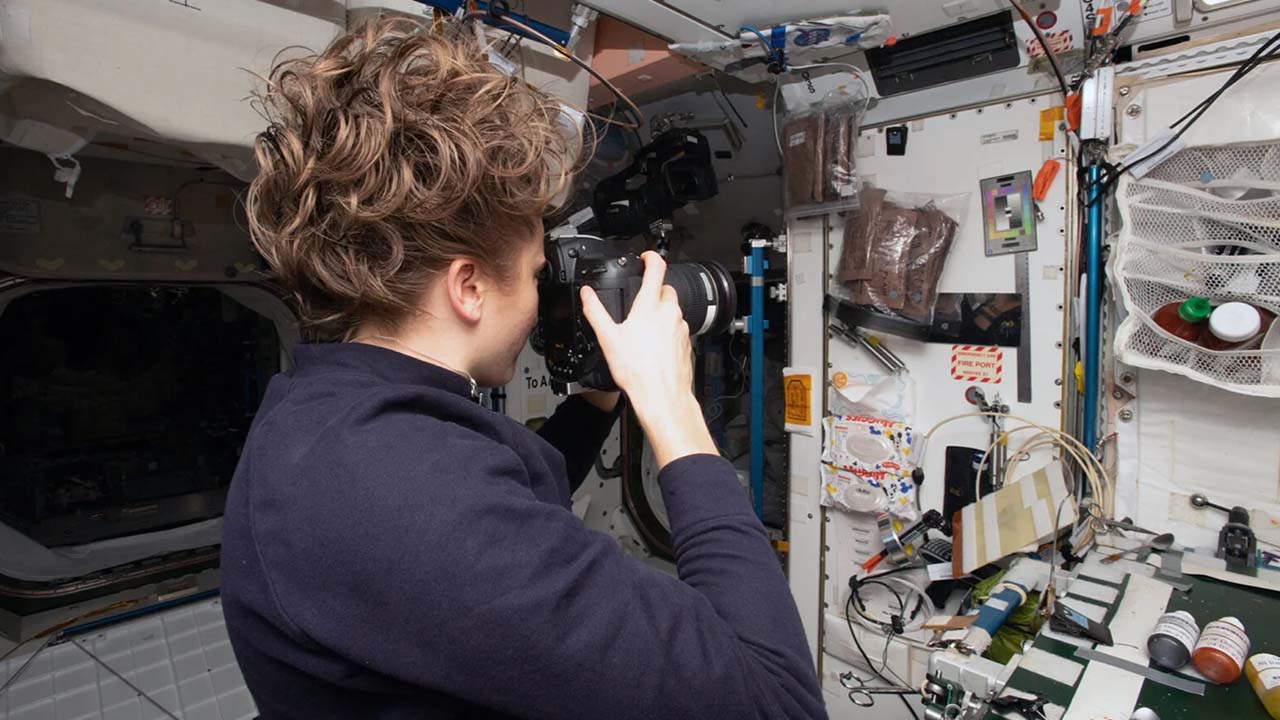

To that end, Walsh and Gorman developed a project sponsored by the ISS National Laboratory in which astronauts photographed certain areas on the space station at specific intervals. The researchers could then use the photographs to see how the astronauts use the tools and spaces. They also used the photos to train software that could help them identify objects in photographs more easily. The software can also be used in archaeological studies in other remote areas, like Antarctic research stations or submarines, to help researchers learn about those environments.

As a result of the project and software’s success, the Walsh and Gorman recently won the Archaeological Institute of America’s (AIA) 2023 Award for Outstanding Work in Digital Archaeology. The AIA is the oldest and largest archaeological organization in North America. Walsh and Gorman were presented with the prestigious award at a ceremony held in New Orleans in January.

The investigation was recognized as the first archaeological study ever performed off planet. By understanding the ways that astronauts have used the space and tools on the ISS, the team hopes the data collected could be used in the design of future spacecraft and habitats to explore the Moon, Mars, and even beyond.

To do the study, the research team had the crew mark off a 1-meter-square space at five different sites in the ISS and photograph each “test site” every day at the same time to study how things changed over a period of time. These types of test site spaces are also used on Earth to help archaeologists in the field study excavation sites and can tell researchers a great deal about how the spaces were used.

Walsh described the project as “studying a microsociety in a miniworld” and hopes that he and Gorman can gain insight into how humans adapt to their environment and achieve a new understanding of how humans use space in space.

“We are revealing aspects of a habitat that people have lived in for more than 20 years, and that the very people inhabiting it 24/7 have not been aware of,” Walsh said.

Because the ISS is not a typical excavation site that you can probe with chisels and brushes, researchers treated the ISS like an archive, sifting through a library of both old and new pictures. The investigation provides sociologists and space historians with a window into what life in space really looks like.

ISS crew members marked off sample sites around the space station as part of the SQuARE archaeological investigation to study how astronauts use objects in space over a period of time.

Media Credit: Image courtesy of NASA

Some have described the emerging field of space archaeology as having to do with human activity in space or activities that further the goal of exploring space. But Walsh has something different in mind. He is more interested in how astronauts interact with and change the objects and spaces inside the ISS.

Walsh also noted that this new innovative approach to the study of archaeology has benefits beyond space. It could also help researchers study places like polar research stations, submarines, and even places like the summit of Mount Everest.

These types of destinations are important to study but are difficult to reach. And while the ISS has enjoyed continuous habitation for more than 20 years now, it is reaching the end of its life span. When that date arrives, the orbital outpost’s legacy will need to be preserved, and Walsh and Gorman are hoping to do that through their project.

“We’re very proud of this recognition,” said Walsh. “We will continue to work on innovative approaches to understanding human behavior and adaptations to life in space.”