The 2022 SmallSat Symposium was held the second week of February in Mountain View, California. Similar to pre-COVID years, the well-attended event covered a broad range of important topics, including constellation updates, satellite launches, orbital and ground infrastructure, Earth observation data and analytics, communications services, and regulatory and funding environments. While it was great to return to the in-person event, the conference vibe was somewhat dampened relative to the last year’s virtual event as the industry has moved from the excitement of SPAC (special purpose acquisition company) mergers and related capital access to realistic discussions of industry growth drivers and structural dynamics.

Growth Observations

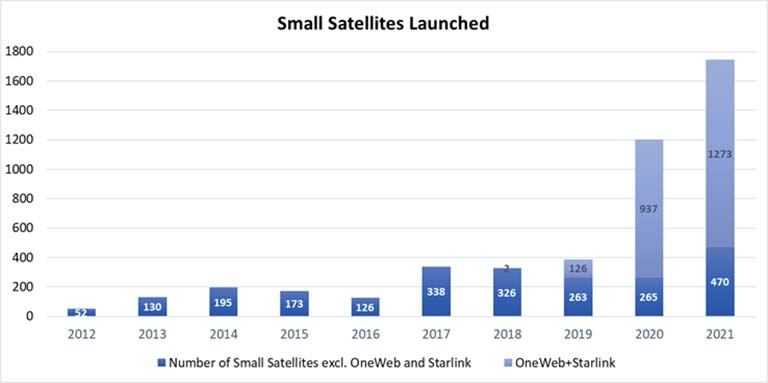

From an operational and business execution perspective, during 2021, the small satellite industry continued to grow at a healthy pace with the number of small satellites (<600 kg) launched increasing 45% year over year, per BryceTech’s data. Progress continued this year—capital raised in the industry was deployed, technology platforms were implemented, satellites were launched, and products were developed. The year 2021 saw not only a record total number of small satellites deployed by large constellations but also record annual numbers aside from the Starlink and OneWeb fleets. The number of small satellites launched outside of these two constellations increased an impressive 77% on a combined basis.

Media Credit: Image courtesy of BryceTech data

As per symposium content, the small satellite industry and the broader space startup ecosystem has become several times more robust than five to six years ago. However, outside of mega constellation deployments and the growth achieved in 2021, some of the acceleration expected in the industry a few years ago has yet to play out, thereby continuing to raise questions on the supply-demand match in the launch and manufacturing value chains. Per a symposium presentation from NSR, there are currently 140+ non-GEO constellations in the works. However, Quilty Analytics reviewed around 300 constellations proposed over the past several years and determined that only 80 or so of these constellations remain active. Furthermore, only about half of this sub-group was found to have sufficient financial resources to make material progress.

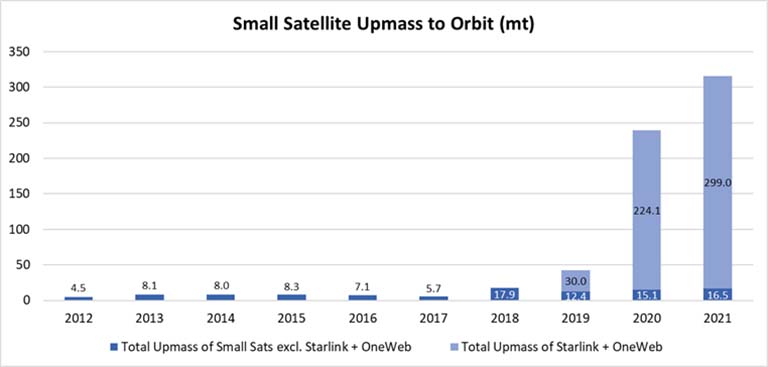

Although small satellite upmass to orbit has increased close to 18 times from just three years ago, it remains heavily concentrated in two mega constellations. Starlink and OneWeb account for close to 95% of the combined upmass of the 1,743 small satellites launched in 2021. Cost declines and growing competition on launch markets are obviously not new news, but this is the first time we heard from a conference stage the mention of rideshare costs at below $5,000/kg. As voiced on panel discussions at the symposium, small launch providers appear to be taking different approaches. Some are attempting to balance their new supply coming online with growth in market demand, while others appear to be taking a riskier path toward “build it, and they will come” to drive market disruption. In terms of the outlook on bulk mass to low Earth orbit, it is important to highlight that SpaceX’s Starship continues to make progress toward a more than magnitude lower cost per kilogram to orbit.

Media Credit: Image courtesy of BryceTech data

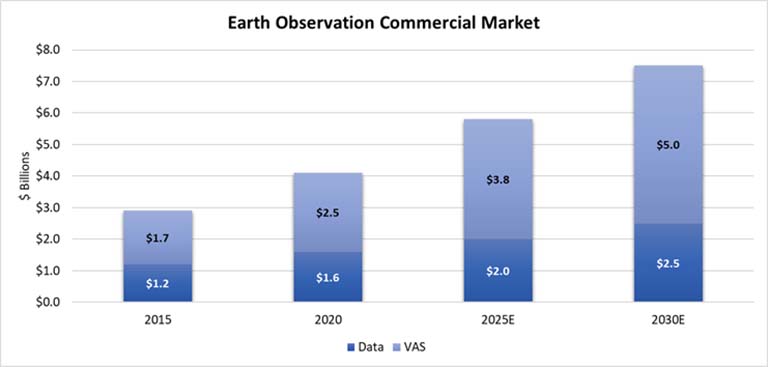

In terms of the Earth observation markets, discussions continue around required resolution levels, revisit rates, analytics capabilities, and pricing models to drive growth. At the symposium, there were discussions of increased openness by significant geospatial data analytics users such as the National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency to use commercial products (as long as the expected level of accuracy is known), which is a positive for the industry. And there remains opportunities for higher-resolution and higher-quality products to continue to take market share. However, the acceleration of overall market demand beyond the mid-single digit growth rates seen in recent years was not apparent from the symposium commentary. Getting to new programs of record in the defense industry will take time. Per Euroconsult data presented at World Satellite Business Week this past December, about 70% of data revenue has continued to emanate from the defense industry. Furthermore, more than 50% of global data revenues, as well as more than 30% of services revenues, were generated by the top two players in the respective segments. There is clearly pressure on the recently publicly listed Earth observation companies to show end-market traction and expansion in customer adoption to deliver on the growth expectations provided to public markets. At the time of the SPAC merger announcement, these growth expectations amounted to mid to high double digit, if not triple digit, cumulative annual growth rates from 2021 to 2025.

Media Credit: Image courtesy of Euroconsult data, December 2021

Following the drumbeat from years prior, a growing number of conversations focused on the risks around already existing and further growth in space debris, as well as lack of related global oversight and accountability. A list of challenges a mega constellation could pose is well exemplified by the recent NASA letter to the Federal Communications Commission regarding SpaceX’s planned 30,000 satellite Starlink constellation. In addition to constellation plans from Starlink, Amazon Project Kuiper, and OneWeb, we have seen recent startup announcements with plans for up to 100,000 satellite constellations, as well as several foreign ITU (International Telecommunication Union) filings proposing constellations of hundreds of thousands of satellites. The damage done by recent anti-satellite tests has been broadly discussed. At the same time, revenue models to support scale up of debris removal remain uncertain, and some of the technology complexities are yet to be solved. Given the imminent increased congestion, various technologies around debris tracking and SSA (space situational awareness), fleet management, autonomous operations, as well as in-orbit servicing are likely to see growing demand tailwinds in the coming years. Initiatives such as the U.S. Space Force’s SpaceWERX Orbital Prime in maturing relevant capabilities remain very important.

Financial Markets and Structural Outlook

Per some of the investor commentary at the symposium, there is still plenty of capital available for early-stage space companies despite the general stock market underperformance of the recently de-SPACed and now public space companies. In recent weeks, we have seen the announcement of a $50 million seed round toward a new constellation, as well as completion of several sizable later stage VC rounds in an ecosystem that is much more robust and better capitalized than a few years ago. However, looking at the historic examples (telecom, dot com, cleantech, etc.) a prolonged discrepancy in public-private market valuations is unlikely, and public market valuations and investment appetite will affect private markets over time. It is also clear that the capital raised by SPACs has been competing with other private sources of capital and is affecting valuations in funding still early-stage space companies. While additional space SPAC transactions are expected in 2022, particularly given that the large amounts of capital raised by various acquisition companies are yet to be deployed, access to PIPE (private investment in public equity) capital has declined significantly, and investor redemption rates on SPAC mergers have surged.

The question here is when some of these recently listed space companies will reach performance levels meeting and beating the reduced public investor expectations thereby establishing a floor to the recent price declines, and whether or when the broader markets care to start differentiating between winners and losers. Per symposium panelist commentary, it is unclear whether the publicly listed company performance has bottomed yet. It is also fair to assume that a prolonged volatility here will be a distraction not just to management teams but also employee base and the ability to recruit the talent to deliver the promised growth.

Media Credit: Image courtesy of NASDAQ stock price data; CASIS analysis

This leads to the question of structural change in the industry. In 2021, we already saw an increase in the industry M&A activity, including the de-SPACed companies using their new currency and cash to strengthen technology position or expand revenue base, or private equity rolling up smaller companies in various value chains. Per symposium panelist commentary, more M&A is expected as the capital access via SPACs will tighten, and the recently listed companies will need to raise additional capital thereby catalyzing consolidation. Most of the space companies that went public via SPAC transactions likely had intended to raise sufficient funding to reach sustained profitability. However, symposium panelist commentary pointed to an expectation of about one-third to one-half of these companies will need to raise additional capital over the coming years.

Investor dialogue at the symposium also brought some commentary on the topic of private space stations, with recognition of geopolitical drivers, the government’s continued demand for manned spaceflight, and government interest to move such capital-intensive endeavors off its balance sheet. However, given the timeline, cost, and deployment risks associated with such assets, there were questions raised as to whether such opportunities are compatible with typical venture capital investment timelines, whether this is selectively a domain for private equity, or whether the government would still need to take a significant lead in funding such infrastructure.